Links and Thoughts #6 (June 2024)

– personal

This month’s compilation brings an essay by a famous startup investor about how to do “great work” in any field, a critical essay about Winston Churchill, an overview of the potentially groundbreaking research of biologist Michael Levin, a summary of statistics showing that a small group of repeat offenders disproportionately commit most of the crime, an article about how gerontocratic policies affect young people in modern societies and what to do to fix the problem, and an explanation of how much weight we should give to hypocrisy as evidence against the views of the hypocrites.

How to Do Great Work

- Link to article

- Author: Paul Graham

- Date: 2023-07

- Source: Paul Graham (personal website)

Paul Graham, known for being one of the founders of Y Combinator, wrote this essay explaining the general recipe for doing great work in any field. Great work takes many forms, but in general, it’s characterized by greatness in ambition and impact; in the best cases, the result is the creation or discovery of an entirely new field. It should go without saying, but Graham explicitly says that his guide is for very ambitious people. The essay contains lots of practical wisdom and motivation—too much to summarize in a sentence or two. However, I think this quote is the best encapsulation of Graham’s recipe for doing great work:

Curiosity is the key to all four steps in doing great work: it will choose the field for you, get you to the frontier, cause you to notice the gaps in it, and drive you to explore them. The whole process is a kind of dance with curiosity.

Rethinking Churchill

- Link to article

- Author: Ralph Raico

- Date: 2021-11-23 (originally published in 1999)

- Source: Mises Daily, Ludwig von Mises Institute

This essay, by the eminent libertarian historian Ralph Raico, originally appeared in a 1999 book titled The Costs of War: America’s Pyrrhic Victories. Raico provides a critical biography of Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom during the Second World War, citing plenty of high-quality sources. In mainstream history and media, the image of Churchill is that of a hero, a wise strategist, and a principled statesman, widely lauded across most of the political spectrum. Raico’s essay dispels the Churchill myth entirely, exposing him for what he really was: an opportunistic and unprincipled politician, a bloodthirsty and short-sighted war criminal, and one of the godfathers of the destructive Leviathan of the modern welfare-warfare state.

A Revolution in Biology

- Link to article

- Author: Kasra

- Date: 2024-06-08

- Source: Bits of Wonder (Substack)

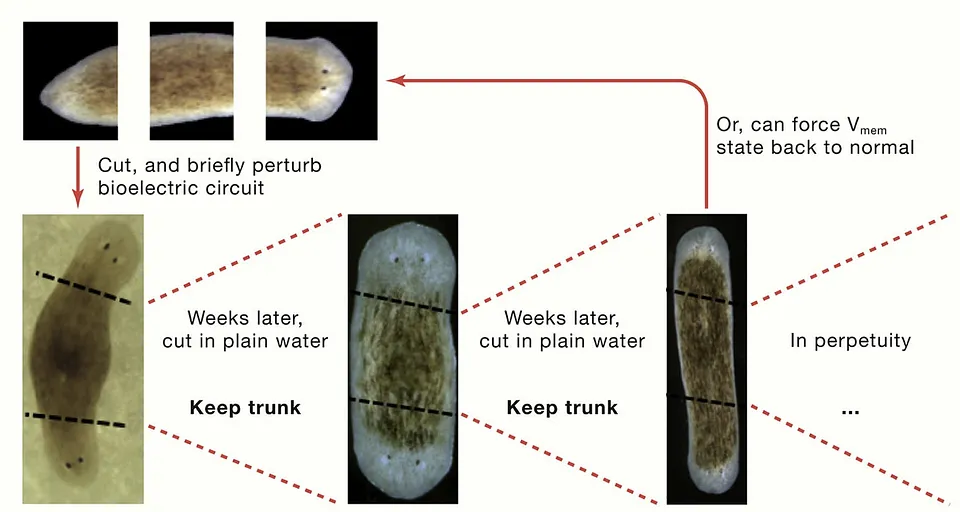

This article is an overview of the potentially groundbreaking work of Michael Levin and colleagues in developmental biology. Levin and colleagues’ central claim is that, while genes are still important, higher levels of abstraction and control meaningfully exist in biology; the bioelectric network of the organism is an example of that. It turns out that all cells, not just neurons, produce and sense electric signals in order to coordinate behavior and encode information.

Levin’s lab has demonstrated that the bioelectric network stores anatomical information independently and that it’s possible to modify the structure of an organism just by modulating its bioelectric network, leaving its genes intact. For example, they have induced planarian worms to grow two heads or no heads at all, and frogs to grow extra limbs or even a functional eye in their tail. Beyond the myriad practical applications this research could have in the long run, Levin’s work suggests that the definitions of agent, intelligence, and creativity should be broader, encompassing lower and higher levels of biology in a fractal manner. This is a deep perspective shift that raises some complicated philosophical questions.

When few do great harm

- Link to article

- Author: Inquisitive Bird

- Date: 2023-04-23

- Source: Patterns in Humanity (Substack)

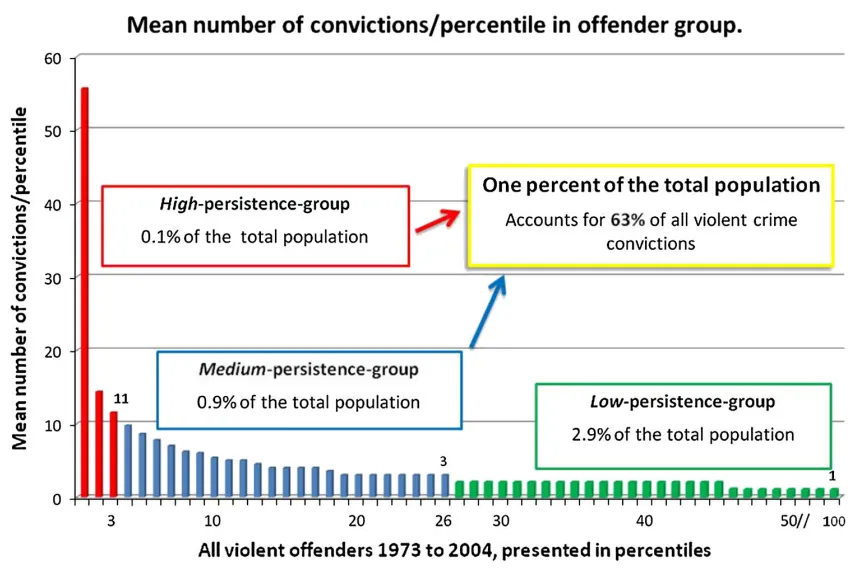

This short article summarizes data from several Western countries, illustrating how a small number of repeat offenders are responsible for a large fraction of the crime. Arrests, convictions, and self-reported delinquent behavior roughly follow power law distributions, in which a few people disproportionately account for most criminal and delinquent behavior. In Sweden, for example, “1% of people were accountable for 63% of all violent crime convictions, and 0.12% of people accounted for 20% of violent crime convictions.” Another example: in New York City, “nearly a third of all shoplifting arrests in the city in 2022 involved just 327 people, who collectively were arrested and rearrested more than 6,000 times.”

Critical Age Theory

- Link to article

- Author: Richard Hanania

- Date: 2024-01-29

- Source: Richard Hanania’s Newsletter (Substack)

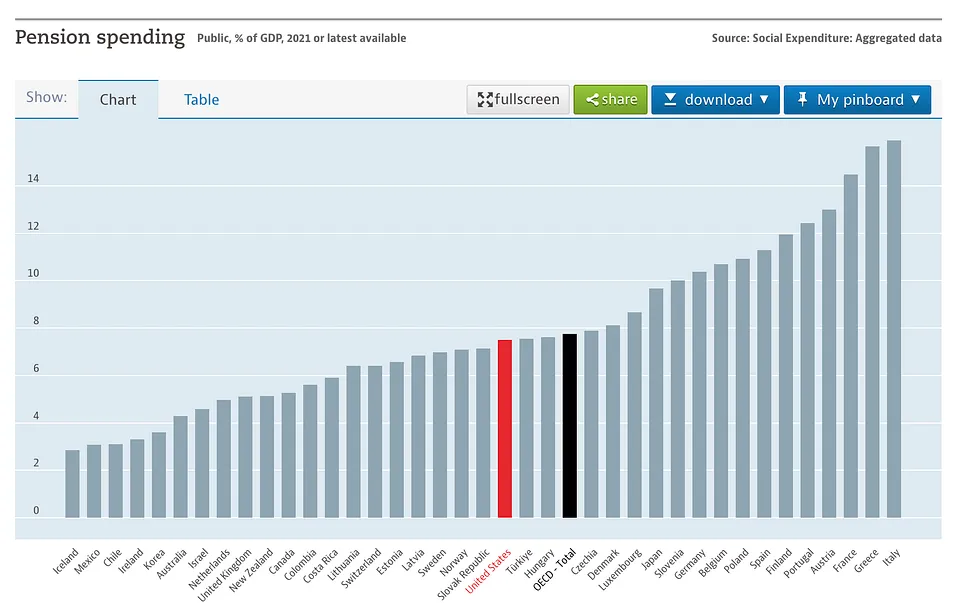

In this essay, Hanania explains the concept of gerontocracy, which is basically government policy that systematically favors the old at the expense of the young, and why it came to exist across modern societies. He also explains how gerontocracy manifests in four broad areas of public policy (government spending, credentialism, employment law, and housing), and how this “has in effect made young people poorer, less likely to have families, and in a state of perpetual adolescence.” In light of the “systemic” nature of this “age privilege,” Hanania makes the case for “Critical Age Theory”1 as an intellectual movement and proposes the following concrete anti-gerontocratic policies:

- Less government spending on entitlements that go to old people

- Fewer government subsidies to education

- Occupational licensing reform

- Giving the youth an even playing field in the labor market by abolishing seniority systems and cutting back or eliminating age discrimination laws

- YIMBYism

- Subsidies for families with children

You Don’t Believe You!

- Link to article

- Author: Bryan Caplan

- Date: 2024-06-26

- Source: Bet On It (Substack)

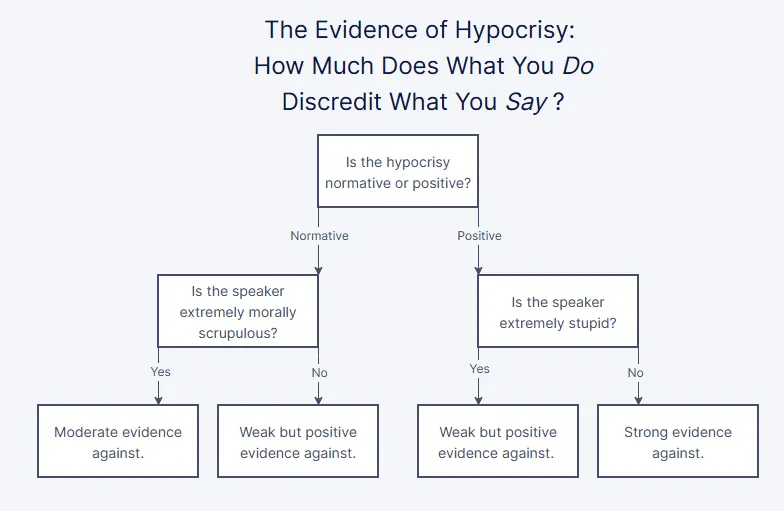

In this short article, Caplan elaborates on his answer to the question of whether someone’s hypocrisy regarding a view provides substantive evidence against that view. Caplan argues that this depends primarily on the type of hypocrisy in question:

- Normative hypocrisy is when someone’s moral views clash with his behavior. This provides evidence that the person is morally flawed, but it doesn’t provide much evidence that his view is incorrect.

- On the other hand, positive hypocrisy is when someone’s descriptive views clash with his behavior. This does provide strong evidence against the view because it shows that the person himself disbelieves it.

Caplan also provides some caveats:

- If we have independent knowledge that the person is extremely morally scrupulous, then normative hypocrisy does provide moderate evidence that his view is incorrect, because it should make us doubt that he actually believes it; of course, it should also make us doubt our previous judgment of his scrupulousness.

- On the other hand, if we have independent knowledge that the person is extremely stupid, then positive hypocrisy provides only weak evidence against the view.

Footnotes

-

This term is a tongue-in-cheek reference to critical race theory (CRT), which is basically the application of critical theory to the academic study of race in society, politics, and media. Thus, in concrete terms, CRT seeks to expose, explain, and critique alleged social, political, and legal “power structures” that “oppress” certain races and “privilege” others; it considers that “racism” is systemic to various aspects of those power structures and that it’s not only based on individuals’ prejudices; and it argues that these racial biases are what causes racial disparities in outcomes. Evidently, CRT is a fundamentally leftist (i.e., egalitarian) academic framework, since from the outset it rejects that there are measurable differences in traits or behaviors among different races that result in different group outcomes, or even rejects that races exist as more than “socially constructed” categories that are pretty much arbitrary. To learn more about what races actually are and why they’re not just arbitrary categories, I recommend reading the article Are Racial Classifications Arbitrary? by Noah Carl. ↩